Physiotherapy for A Climber's Scapholunate Injury: A Case Report

Part I of III covers red flags, how an orthopedic diagnosis compares to a functional assessment, and the importance of early isometrics.

Introduction

Hands, much like a spray-wall, are congested with many overlapping features of bone, tendons, and cartilage. As climbers, the hand is our main interface between the wall and our brain. We need our hands to tell us what holds are before us so as to calibrate and prepare our shoulders, and hips for our next move. So what happens when something goes awry? Today we will do a three part series of a deep dive on climbing injuries to the scapholunate and lunotriquetral joints and why they are so important to assess if you suspect something wrong. This case describes the rehabilitation and return-to-climbing approach on a 24 year-old female climber with a right scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligament injury.

Case Report

When we initially assessed our climber, this is what she had to say.

“I took a bad fall while out climbing on Dec. 17th, 2023, and I landed awkwardly on my left hand. My wrist hyper-extended when I hit the ground and I felt/heard a snap plus had an immediate onset of paresthesia within the median nerve distribution of my left hand. After the injury, I decided to wait 20-30 minutes and monitor symptoms but due to the quick onset of swelling and bruising, worsening pain, and slight nausea I was experiencing, I decided I needed to get medical attention. One of the other members of the climbing group hiked out with me and we went to the ER.”

“Because of the bruising and pain located around that area after the injury I was immediately concerned of a scaphoid fracture. I expected the ER physician to see if this area was tender on palpation (which it was), as well as test for pain with axial load/compression through the thumb (this test was negative).”

Our climber had some really good intuition to go for an ER visit. There was instant swelling and bruising, numbness and worsening pain. As a clinician it is good practice to rule out any serious pathologies (red flags) before ruling in any diagnoses. This is because the complications from a missed fracture will significantly delay healing time, return-to-sport, and serious complications requiring surgery. Below is a list of some complications of a scaphoid fracture that is missed.

Ruling Out A Scaphoid Fracture

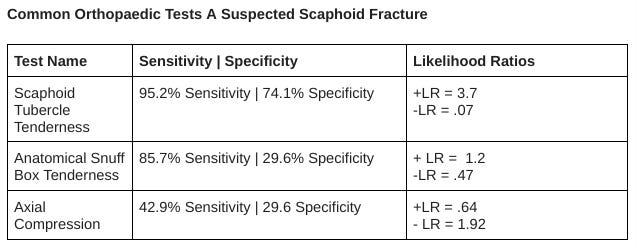

As these complications are concerning, clinicians have developed an evidence based algorithm to determine which tests should be used to rule out a suspected scaphoid fracture.

The text-box explains why you would want to use both sensitivity/specificity AND likelihood ratios. These tests are sensitive but have inconclusive likelihood ratios meaning that even if a climber tested negative (no pain) on tests 1,2 or 3 there should be a follow up with radiographic imaging based on the initial presentation.

Fortunately in our case, the climber was negative on the plain radiographs on the follow-up.

ER X-ray results:

Follow-up X-ray results:

Ruling In A Diagnosis

Just because a fracture is ruled out, it does not mean we are out of the woods yet. If the nature of the injury is not osseous then it could be ligamentous which is also concerning. Remember our ligaments are the ropes that tie our bones together and make sure they are in alignment to optimize absorption and generation of forces. They also have biological sensors to help with our hand-eye coordination in climbing.

Other possible diagnoses include: DeQuervain’s tenosynovitis, or arthritis but they are of low probability based on the acute nature of injury.

Our climber reported this when we interviewed her.

“At the initial time of injury/ER visit, I did expect there to be a fracture but by the time the second round of x-rays came around ~10 days later, I was fairly confident that the injury was ligamentous not bone because the anatomic snuffbox was no longer TOP, and the symptoms I was experiencing (clunking, catching, visible prominence of the lunate) were more representative of an instability rather than a fracture. “

This was confirmed with a visit to a sports medicine physician.

”During my follow up appointment with the sports medicine doctor, he performed these same two tests for the scaphoid, as well stability tests for the DRUJ, scapholunate ligament, and lunotriquetral ligament. Based on these clinical tests, it was determined that I had grade 2 tears of the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments, and a grade 1 sprain to my DRUJ interosseous ligament.”

Without getting into too much detail, these tests were designed to test the stability of the scapholunate, lunotriquetral, and part of the dorsal radioulnar joint. This means that the clinician is moving the injured joint and the adjacent joints in opposite directions and testing for laxity and pain. However, as you can tell from above the general impact of these tests on their own on confirming a diagnosis is relatively small. Which is why the climber’s mechanism of injury, history of pain and function is key to increasing the probability of the diagnosis. Key takeaway is never rely on one test in isolation to make a diagnosis. Bodies are complicated!

So far this is our climber’s current diagnosis:

Grade 1-2 Lunotriquetral Ligament Tear and Scapholunate Ligament Tears

Grade 1 DRUJ (non-specific) → further differential diagnoses could be features around the TFCC (disc) such as ulnar-lunate ligament, volar radioulnar ligament, ulnar-triquetral, ulnar-collateral, DRUJ ligament, ECU sheath and tendon. It is difficult to palpate each individual ligament and have specific stability tests for the DRUJ joint.

Medical Assessment versus Physio Assessment

The purpose of the medical assessment above is to inform an athlete and the physiotherapist of the severity of an injury, orders for when to initiate therapy and what specific exercises to do. A physiotherapy assessment is to determine the current level of function in the athlete, compare it to their baseline function and to determine what steps and timeline is needed for the athlete to return to baseline. Reiman and Thorburg 2014 suggest that objective and physical examinations only contribute up to 30% of the diagnosis whereas the subjective history contributes from 56-90% of a diagnosis. So for the physiotherapist, the overall objective assessment may have low value in diagnosis but have high value building a treatment plan. You can see this below.

Subjective:

The client has had a 4 week history of left wrist pain after falling with bouldering with an out-stretched hand and hyper-extended wrist. There was immediate pain distinct with numbness along the palm of the wrist accompanied by significant swelling within 45 minutes and bruising within 120 minutes. Due to concerns regarding a left scaphoid fracture, the client went to the ER and had an X-ray and splint for 10 days before receiving a follow-up X-ray that cleared her of a scaphoid fracture. After two weeks, the patient stopped using the spica splint. She then saw a sports physician who diagnosed her with a Grade 1-2 scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligament tear, and a Grade 1 DRUJ sprain.

Currently there is increased pain and swelling on the radial aspect of her wrist but no neurological symptoms. Movements that aggravate pain are weight bearing through the palm (wall-push up), gripping in extension or flexion. Pronating and supinating the hand is painful but improving. There is some clunking with combined movements of wrist flexion and deviating side to side. Things that have helped the pain have been ice, rest, and taping.

Objective Findings of the Wrist:

Mobility (Active/Passive Range of Motion):

1- Extension and flexion within functional limits ~65-70 degrees each but more painful on wrist flexion than extension.

2- Supination (palm-up) painful with passive movements more than active.

3- Ulnar deviation was painful

Pain Provocative Tests:

Watson Test: +ve

Distal radioulnar joint instability Test: -ve but painful

Climbing Strength Tests:

Wide pinch (10 lbs) = 5/10 pain

Wide pinch (5 lbs) = 3/10 pain

Analysis from medical assessment:

“At the initial ER visit, the nurse used a plaster spica splint/half cast to immobilize my wrist and thumb due to the concern of a scaphoid fracture. I was supposed to wear this splint for approximately 2 weeks until I returned to the hospital for the second round of X-rays which would either confirm or rule out a scaphoid fracture. I was not very compliant with wearing this splint because it was extremely uncomfortable and resulted in a lot of ulnar and median nerve irritation, and it made my job as a physio very difficult.

After the follow-up X-rays confirmed that there was no fracture, the sports medicine doctor provided me with a brace which was much more comfortable. I was instructed to wear the brace for work and higher impact activities for ~6 weeks.”

Analysis from physiotherapy assessment: The injury to her scapholunate, and lunotriquetral ligaments has led to some instability greatly affecting our climber’s grip strength, and range of motion. This could also be explained from the lack of mechanical loading from no climbing in 4 weeks. As you can see the deconditioning also causes her unaffected arm (right) to lose some grip strength.

When the Physician Signs Off, The Physiotherapy Begins…

Immobilizing and splinting was a key part of early healing, you don’t want complications of chronic loosening of the wrist joints. However, immobilization is actually a game of trade-offs. Yes, you are stabilizing the ligaments and holding them together so that, over time, there will be no laxity and micro-dislocations of the thumb (subluxations). At the same time immobilization of the contractile tissues around the thumb and hand (tendons, muscles, sensory organs) will lead to loss of strength, power and coordination of the hand. This can affect the muscles of the upper quadrant as well as the elbow and shoulder complexes which is why early exercise to areas proximal to the injured joint is essential in maintaining power.

So how do we solve this dilemma? The answer lies in isometrics which is forcing the muscles to contract without moving the joint so that displacement of the healing ligaments are minimized. Remember, ligaments are only used when the joint is moving. In other words, if we don’t move the hand but activate the muscles we can preserve some strength, and power. All this gives us a head start in rehab when the immobilization period ends. Many, many climbers often mistake immobilization as a period of rest and inactivity. This is a huge disadvantage as it could set your time table back from climbing by weeks!

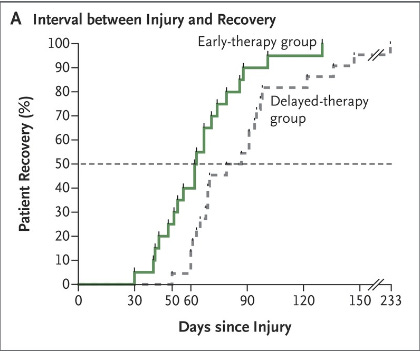

A 2017 study published in the most famous medical journal (New England Journal of Medicine), found that starting rehab 2 days after an injury versus 9 days shortened the timeline for returning to sport by 3 weeks, without any significant increase in reinjury. Extending that logic, waiting a week longer to start rehab leads to ~3 weeks longer for returning to baseline; delaying your rehab by a whole month will lead to a ~3 month delay than usual.

Remember a successful treatment plan cannot occur without a thorough assessment between the therapist and climber. Physiotherapists are much more than people that teach exercises or use machines, we are always racking our brains of other possible diagnosis, complications and coming up with individual progression and regression exercise regimens to optimize your healing!

Summary- TL;DR

Injuries to the thumb and wrist are no joke and should be examined early by a physician or physiotherapist with experience in climbing. Imaging may be required to rule out more sinister complications.

Start your isometric exercises as early as you can with a physiotherapist, it will save you so much time.

Add numbers to how painful certain moves and holds are (from 1-10). This will help your physiotherapist create an optimal load management and return-to-climbing plan for you.

In part two we will dive into the complicated biomechanics of the scaphoid and its utmost relevance to climbing and next steps in our climber’s rehabilitation.

References:

Schmauss, D., Pöhlmann, S., Weinzierl, A., Schmauss, V., Moog, P., Germann, G., ... & Megerle, K. (2022). Relevance of the scaphoid shift test for the investigation of scapholunate ligament injuries. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(21), 6322.

Pickering, G. T., Fine, N. F., Knapper, T. D., & Giddins, G. E. B. (2022). The reliability of clinical assessment of distal radioulnar joint instability. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume), 47(4), 375-378.

LaStayo, P., & Howell, J. (1995). Clinical provocative tests used in evaluating wrist pain: a descriptive study. Journal of Hand Therapy, 8(1), 10-17.

Bayer, M. L., Magnusson, S. P., & Kjaer, M. (2017). Early versus delayed rehabilitation after acute muscle injury. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(13), 1300-1301.

Brigstocke, G. H. O., Hearnden, A., Holt, C., & Whatling, G. (2014). In-vivo confirmation of the use of the dart thrower’s motion during activities of daily living. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume), 39(4), 373-378.

Ferrer-Uris, B., Arias, D., Torrado, P., Marina, M., & Busquets, A. (2023). Exploring forearm muscle coordination and training applications of various grip positions during maximal isometric finger dead-hangs in rock climbers. PeerJ, 11, e15464.

Appendix: