Open Kinetic Chain Exercises are Key to Address Knee Strength Deficits

Part 1 of 3 Things I Learned from Mick Hughes' ACLR Webinar

There is a widespread and misguided fear that open kinetic chain (OKC) exercises will lead to graft damage and rupture. On the other hand, closed kinetic chain (CKC) exercises are assumed to be safer and superior as they impart functionality and sport specificity. The goal of this article is to convince you that OKC’s safe and necessary for successful ACL rehabilitation (ACLR) to occur.

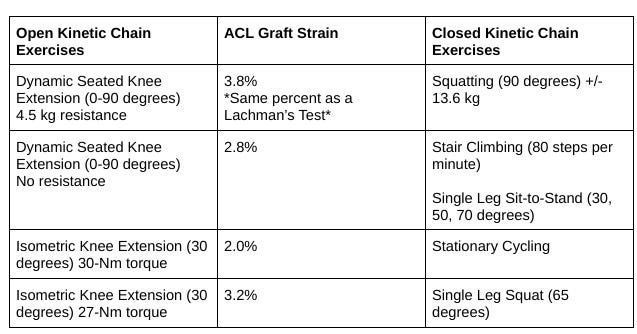

The 2023 Aspeter ACL Guidelines finds no contraindication for the initiation of OKC exercises (90-45 degrees) after 4 weeks. Below is a comparison of OKC and CKC exercises and the amount of graft strain performed.

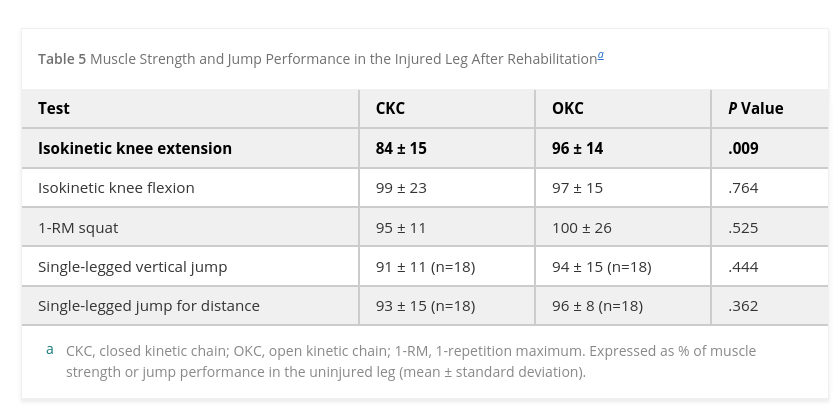

When the clinician finds significant deficits in knee strength in their client, whether during the program or post-program, it is essential to address exercises that bias specific muscle groups instead of functional/CKC exercises. A Swedish study in 2007 found when compared solely OKC vs. CKC cohorts that the OKC group had significantly higher isokinetic knee strength measures than the CKC group. Functional strength measures such as the squat, vertical and horizontal jump yielded no differences. Why is that the case?

Functional exercises such as lunges and squats utilize other large muscle groups such as the trunk, hip and ankle muscles to compensate for the muscle weaknesses of the knees. This perpetuates the problem of underloading the quadriceps muscle and helping the patellofemoral and tibiofemoral cartilage maladapt to the impact forces of sport, thus increasing the risk of injury and osteoarthritis.

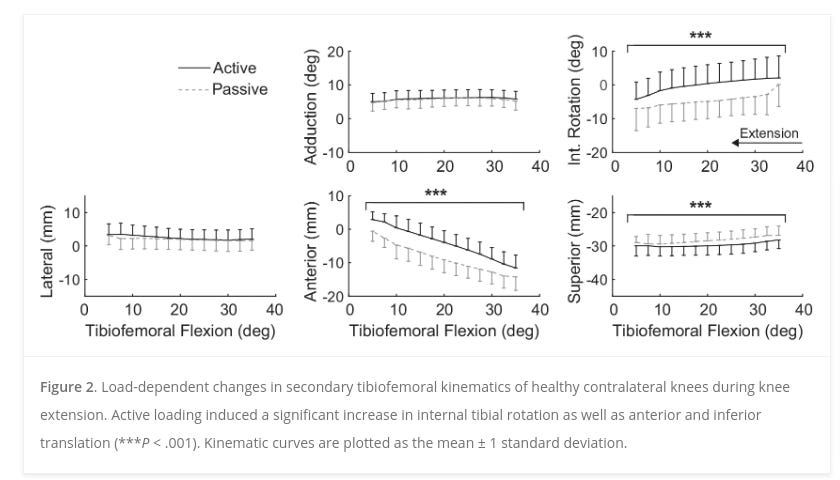

A 2022 study by Hipsley et al.from the University of Melbourne found that quadriceps strength 2 years post ACLR had a moderate inverse correlation (r of ~.78) with tibiofemoral cartilage volume. Knee strength was determined from knee extension torques of between 40-60 degrees of flexion. A high tibiofemoral cartilage volume (indicative of knee underloading) is proposed to be a risk factor for the development of osteoarthritis years after surgery.

This also appears to be true for the patellofemoral joint (PFJ), a 2023 study by Liao et al. from Michigan-Flint found ongoing underloading of the PFJ three years post ACLR, with the contact pressure of the non-surgical also underloading to achieve symmetry of the surgical leg. Hipsley et al.’s biological explanation for the expansion of cartilage is due to a lack of proteoglycans (from underloading) and the contribution of excess edema in the joint space.

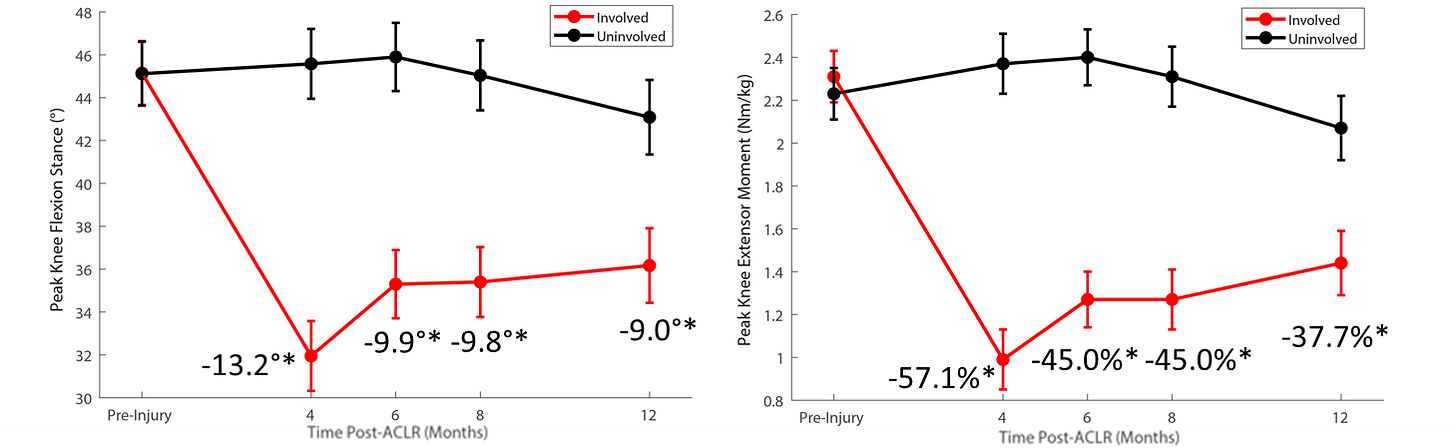

It appears that biomechanical alterations in running can persist even five years after surgery. In the graph below from Knurr 2019, one can see how at 12 months post ACLR there is 37.7% difference between knee extensor strength. A 2019 systematic review reports suggests that the lack of instantaneous knee extensor strength and power changes the loading and contact pattern of the knee, perhaps this explains the overall underloading of the knee in running and persistent pain over time.

As running is an essential movement to all sports, quadriceps deficiencies may potentially be a significant source of poor outcomes for return-to-sport post-ACLR. Again the authors point to isolated knee strengthening and extensions as a key therapy to mitigate the poor outcomes related to ACLR.

This is the first lesson imparted by Mick Hughes— do not be afraid to prescribe OKC exercises once the ACL graft is stable. It is a simple, yet key ingredient to a successful and healthy knee after surgery!

References:

Jewiss, D., Ostman, C., & Smart, N. (2017). Open versus closed kinetic chain exercises following an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017.

Liao, T. C., Bird, A., Samaan, M. A., Pedoia, V., Majumdar, S., & Souza, R. B. (2023). Persistent underloading of patellofemoral joint following hamstring autograft ACL reconstruction is associated with cartilage health. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage.

Kotsifaki, R., Korakakis, V., King, E., Barbosa, O., Maree, D., Pantouveris, M., ... & Whiteley, R. (2023). Aspetar clinical practice guideline on rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(9), 500-514.

Forelli, F., Barbar, W., Kersante, G., Vandebrouck, A., Duffiet, P., Ratte, L., ... & Rambaud, A. J. (2023). Evaluation of Muscle Strength and Graft Laxity With Early Open Kinetic Chain Exercise After ACL Reconstruction: A Cohort Study. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 11(6), 23259671231177594.

PAULOS, L., & ANDREWS, J. R. (2012). Anterior cruciate ligament strain and tensile forces for weight-bearing and non–weight-bearing exercises: a guide to exercise selection. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 42(3), 209.

Buckthorpe, M., La Rosa, G., & Della Villa, F. (2019). Restoring knee extensor strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical commentary. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 14(1), 159.

Tagesson, S., Öberg, B., Good, L., & Kvist, J. (2008). A comprehensive rehabilitation program with quadriceps strengthening in closed versus open kinetic chain exercise in patients with anterior cruciate ligament deficiency: a randomized clinical trial evaluating dynamic tibial translation and muscle function. The American journal of sports medicine, 36(2), 298-307.

Pairot-de-Fontenay, B., Willy, R. W., Elias, A. R., Mizner, R. L., Dubé, M. O., & Roy, J. S. (2019). Running biomechanics in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 49, 1411-1424.