How To Deal With Abdomen Pain In Running

One of the biggest complaints when runners first pick up the sport is pain in the abdomen particularly after drinking or eating. This…

One of the biggest complaints when runners first pick up the sport is abdomen pain particularly after drinking or eating. This phenomenon known as the “stitch”, can affect about 30–50% of runners. Why does it happen and is there something that you do to halt it? This article reviews the potential causes of exercise-related transient abdominal pain, and provides some useful strategies to mitigate its intensity.

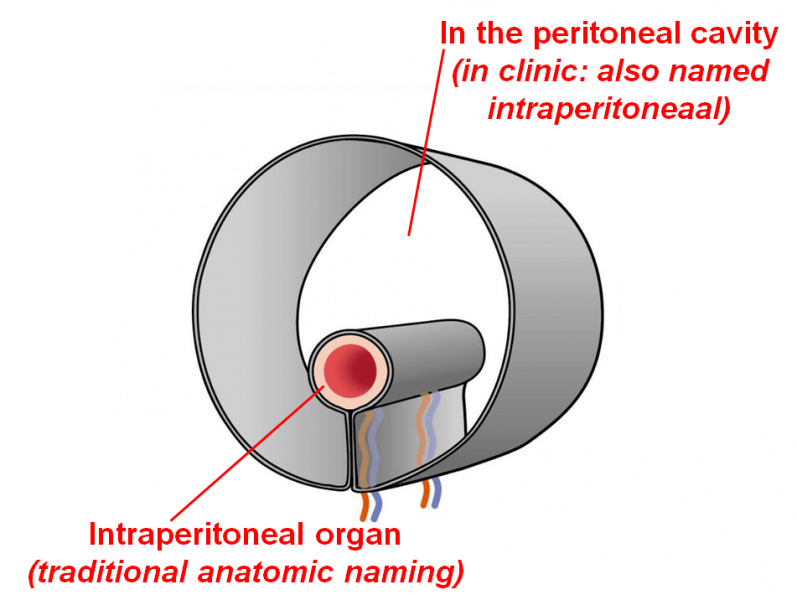

Describing The Peritoneum

Your gut is a long convoluted tube that exists in an empty space called the peritoneum. The two are connected by bands of protein known as peritoneal ligaments. A vast system of nerves known as the enteric nervous system innervates your gut to help move food, and absorb nutrients. When you eat food, it takes often four hours or more to get digested and make its way through the gut. When you drink water it may take up to an hour. In studying the stitch, scientists have come down to two main theories.

The Peritoneal Ligament Theory. Stitch is caused by the gut pulling on the peritoneal ligaments. When you have fluid or food in the gut, it increases the guts weight and pull on the peritoneal ligaments. If you combine both the vigorous movement of running and an increased weight on the gut, it may irritate the nerves of the enteric nervous system causing the stitch, a sensation of cramps, discomfort and pain.

The Ischemic Gut Theory. Your gut also is nourished by a vast array of blood vessels stemming from the aorta. However, there is a limited blood supply in your body. You need blood for your gut to aid in digestion, and you also need blood to deliver oxygen to your muscles for fuel. Both muscle and gut compete for this limited blood supply but where the blood will go is determined by the demands of the body. If you have eaten a large meal more blood will go to help the gut and less to the muscles. And vice versa, if you are exercising more blood will go to the muscles and less to the gut. So what happens if you run with food or fluid in your gut? As you are forcing your body to move, more blood will go to the muscles as they take precedence over the gut. However that isn’t without a cost, as not all the blood can leave the gut that is digesting food. This decreased blood flow causes ischemia in the gut, leading to pain and cramps perhaps as a means of signalling to the brain that there are nutrients to be absorbed and that you shouldn’t be running.

Separating Fact from Conjecture

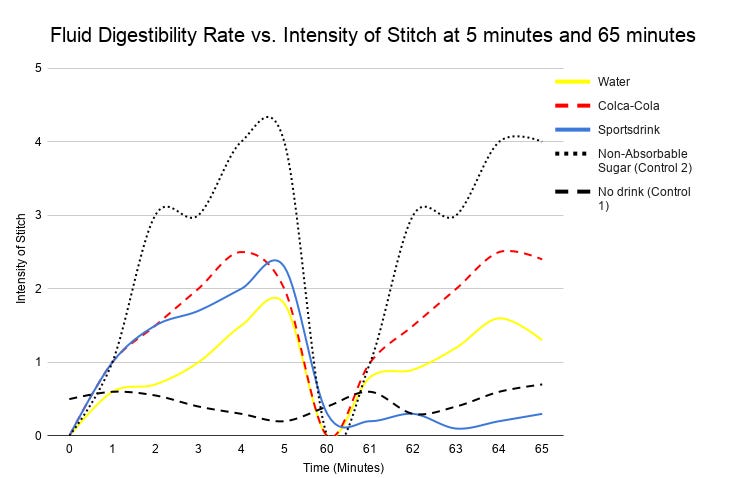

To determine which theory was correct, Plunkett and Hopkins published a very famous study in 1999. To see if the Ischemic Gut theory was true they took 10 subjects and made them run on a treadmill on four separate times, each with time with a different liquid with differing absorption rates (water, a sports drink, Coca-Cola, and a non-absorpable sugar).

If the changes in blood flow were the culprit for stitch then symptoms of pain and cramping should develop slowly and its intensity related with the absorption of the fluid with the non-absorpable sugar causing the most pain and the sports drink the least. If this was false, and the Peritoneal Ligament theory was true then stitch should occur quickly at the onset of any fluid that increases the weight of the gut and should persist with a fluid that was slowly digested.

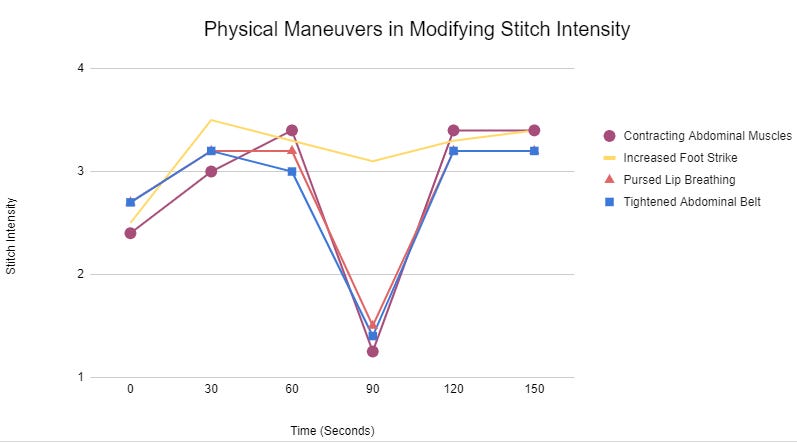

Moreover, the authors cleverly added an additional experiment that would support the ligament hypothesis and challenge the ischemic gut hypothesis. They took another seven subjects, had them run then ask them to perform four different maneuvers that would decrease tension in the peritoneal ligaments but also shunt blood away from the gut. The four maneuvers were: modified breathing, running with heavier steps, contracting the abdomen, and wearing a tight waist belt. Subjects exercised in 5 minute intervals five times, so to observe the time effects of digestion and the change in blood flow from the gut to the muscles.

I summarized their results in two graphs and the following observations can be made from the results.

The digestion rate of water is slower than a sports drink as a similar intensity of stitch is still seen after an hour compared to the sports drink.

The ischemic gut theory is less favorable because the onset of stitch occurs similarly in both time frames. It takes time for blood to shunt away from the gut to the muscles and the opposite effect was observed at 5 minutes.

3. Decreasing the tension in the peritoneum will improve the symptoms of stitch. This can be achieved through breathing through pursed lips (try to blow out a candle), or wearing a tightened belt around the waist.

Conclusion and Suggested Solutions for Stitch

While there are several other theories for stitch, it appears that the Peritoneal Ligament theory plays a major role. There are two important concepts I want to leave behind that will help you reduce stitch in running.

Concept 1: Ensure that the gut is nearly empty to reduce ligament tension

Don’t exercise straight after a meal or large drink for at least 2–3 hours. If you are re-hydrating during exercise, take small amounts frequently. This practice will reduce the mass of fluid in the stomach.

Sports drinks may cause less stitch than water, and may be the preferred fluid when hydrating over a long run. Given that there are so many drinks (ie Hydralyte, Gatorade) in the market it is worth while to experiment with them to see their individual effects.

Concept 2: Practice physical maneuvers to decrease ligament tension during stitch

When you get stitch and practice pursed lip breathing or try wearing an adjustable waist belt. Contracting your abdominal muscles may appear difficult to achieve.

Disclaimer: The content on this site is provided as an information resource only, and is not to be used as a substitute on for any diagnostic, treatment purpose, or professional medical advice. Using the information on this post or links is at the reader’s own risk. Readers should not ignore, or delay in obtaining medical advice for any medical condition they may have, and should seek the assistance of their health care professionals for any such conditions.

References:

Dimeo, F. C., Peters, J., & Guderian, H. (2004). Abdominal pain in long distance runners: case report and analysis of the literature. British journal of sports medicine, 38(5), e24-e24.

MIT Education. Date Unknown. The Tempest. Accessed on March 30, 2020: http://shakespeare.mit.edu/tempest/

de Oliveira, E. P., Burini, R. C., & Jeukendrup, A. (2014). Gastrointestinal complaints during exercise: prevalence, etiology, and nutritional recommendations. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 79–85.

Morton, D. P., & Callister, R. (2002). Factors influencing exercise-related transient abdominal pain. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 34(5), 745–749.

Plunkett, B.T., & Hopkins, W. G. (1999). Investigation of the side pain” stitch” induced by running after fluid ingestion. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 31(8), 1169–1175.